How Meta’s new Content Moderation Policies affect Gender-based Violence

Key takeaways

Toxicity surged before moderation changes: A rise in toxic language began in mid-December 2024, peaking during the holiday season, prior to the January 7th moderation policy change.

Elevated toxicity sustained post-policy shift: After Meta changed its new moderation policies in January 2025, average daily toxicity remained significantly elevated, stabilising at 30-40% higher than levels observed in November 2024.

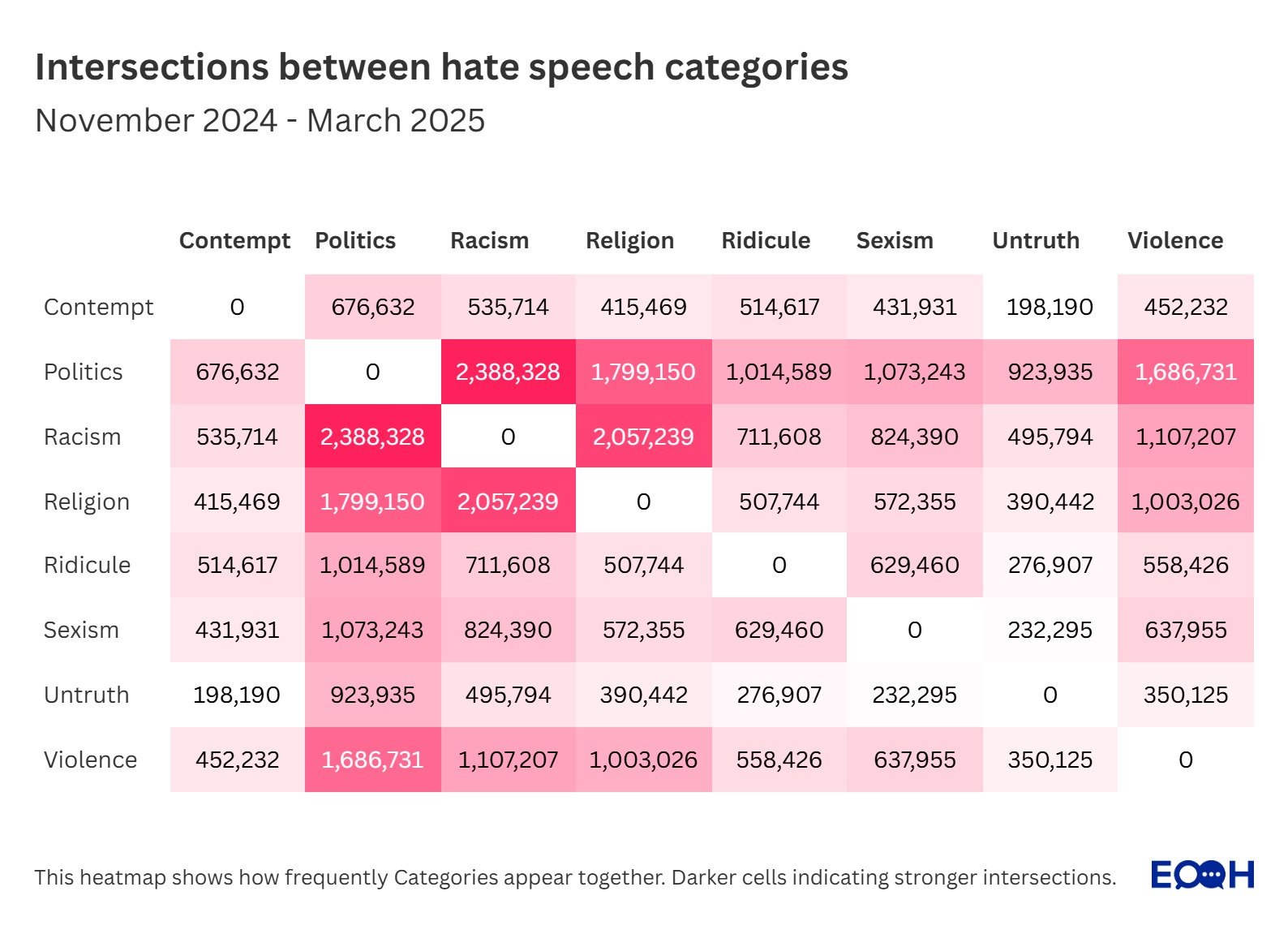

Gendered hate is deeply intersectional: The strongest content overlaps in the sexism baseline were with politics and racism (2.3M words), followed by racism and religion (2M words), underscoring the compounded risks faced by women from marginalised groups.

Online abuse has offline consequences: As digital platforms become less regulated, technology-facilitated gender-based violence risks worsening gender inequality, silencing women, and undermining democratic participation.

Technology-facilitated gender based violence is escalating: technology-facilitated gender-based is not a new phenomenon, but it has accelerated rapidly in recent years.

On January 7th 2025, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta-owned platforms will “get rid of a bunch of restrictions on topics like immigration and gender”, admitting that “we’re going to catch less bad stuff”. The stated goal of Meta’s CEO is to reduce erroneous content takedowns, ensure ‘free expression’, and reduce opportunities for false positives in automatic content flagging.

After this announcement, Meta ended its fact-checking programme, a third-party programme involving 80 trusted media organisations tasked with assessing the accuracy of information circulating on the platforms. Following the example of X (previously Twitter), ‘Community Notes’ were established, a community-driven system which relies on contributors from the community, rather than professional fact-checkers, to add more context to posts that are potentially misleading or confusing. Additionally, Meta removed several content policies concerning immigration and gender. For example, a new section of their policy around hateful conduct started to allow “allegations of mental illness or abnormality when based on gender or sexual orientation, given political and religious discourse about transgenderism and homosexuality”. Meta wrote that although people may use insulting language or call for exclusion when discussing topics such as transgender rights, “Our policies are designed to allow room for these types of speech.”

Users are now allowed to, for example, refer to “women as household objects or property” or “transgender or non-binary people as ‘it”.

Following Meta’s announcement to change their content moderation policy, we launched an investigation using the EOOH dashboard to assess whether toxic language targeting women has increased.

This analysis is based on 230,094 posts on Meta’s platform Facebook and evaluates the evolution of average daily toxicity in the Sexism baseline channel. Baseline channels are specialised data streams that collect posts on topics known to attract hateful content regularly. To avoid bias in data collection, each channel uses neutral keywords (in all EU languages) drawn from the semantic field of its topic. For the Sexism channel, these include terms such as woman, man, men, women, and girls.

The timeframes span from the 1st November 2024 to the 31st March 2025, a period encompassing the platform’s shift in moderation policy that started on January 7th 2025. Specifically, we wanted to assess whether toxic language targeting women increased following Meta’s changes in content moderation policy. By comparing toxicity levels before and after this policy change, we aim to determine whether reduced content oversight and more lenient rules correlated with measurable increases in harmful discourse toward women.

Toxicity began rising sharply in mid-December, peaking during the final two weeks of the month. Following the moderation change in early January, toxicity levels remained elevated, stabilizing at rates 30 - 40% higher than in November. This suggests that reduced oversight may have contributed to an elevated toxicity in the analysed messages. In early December, Meta’s top executive had already raised doubts over its strict moderation system, publicly acknowledged that the company was “mistakenly removing too much content” and that “error rates are still too high,” calling for greater leniency in enforcement to avoid suppressing political speech. These comments, preceding Zuckerberg’s official policy shift, possibly prompted anticipatory posting behavior in our data set. The visible surge in toxicity during this window aligns with a loosening of enforcement attitudes at the top levels of Meta leadership. These findings are consistent with recent research examining the impact of Meta’s policy changes on users’ online experiences. Researchers found that 76% of women reported an increase in harmful content, while 1 in 6 respondents said they had been subjected to some form of gender-based or sexual violence on Meta platforms.

The most heated topics

We also investigated which semantic categories most frequently intersected within the sexism baseline. By categories, we refer to thematic groupings of language commonly associated with hate speech, such as politics or racism, based on lexicon analysis. Each category captures distinct forms of harmful or inflammatory expression. This allows us to identify patterns in how categories co-occur within gender-based online hate speech. The numbers indicated in the graphs reflect how many times the different categories co-occur in the same post.

The strongest intersection was found between politics and racism, with 2,388,328 words, showing significant overlap or “co-occurrence” of these two categories in the dataset. The intersectionality of hate between race, gender, and politics is well-documented. Women with intersecting identities are the most vulnerable online. During elections, female politicians of colour are the target of the most violent online abuse. For example, in the 2020 election period in the U.S., “women of color candidates were twice as likely as other candidates to be targeted with or the subject of mis- and disinformation compared to their white counterparts”. Female journalists and activists are also subject to disinformation campaigns and ‘gender trolling’, with a deliberate strategy of silencing their voices and discouraging them from holding positions of power.

Racism and religion followed closely, with 2,057,239 words, highlighting how racial and religious hostility frequently co-occur in online environments. Additionally, religion-related discourse and politics were also correlated with each other, with 1,799,150 posts. These findings are in line with research indicating that women with intersecting identities - ethnic or religious - are disproportionately targeted by gendered disinformation and hate speech.

These findings underscore ongoing challenges for social media platforms in addressing intersectional harm. Facebook and Instagram have repeatedly failed to ensure a safe environment for marginalised users, particularly women of colour, LGBTQ+ communities, and religious minorities, as reported by several studies. In the absence of robust moderation and accountability systems, these platforms continue to expose already vulnerable groups to unchecked harassment.

Technology-facilitated gender based violence is not new

The digital revolution created opportunities for women to connect, find jobs, and raise awareness of shared challenges and systemic inequalities. Unfortunately, it is increasingly facilitating repression and stigmatisation towards women. Technology-facilitated gender based violence (TFGBV) is not a new phenomenon, but it has accelerated rapidly in recent years. TFGBV refers to any harmful act enabled or amplified by digital technologies, causing physical, psychological, social, or economic harm. Examples of TFGBV include online harassment, cyberstalking, and image-based abuse. Data over time reflects this growing threat: in 2014, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) reported that 11% of EU women had experienced cyber harassment since the age of 15. By 2017, 23% of women surveyed reported at least one episode of online abuse. A 2023 FRA report identified women as the most targeted group of online hate, with peak rates ranging between 16% and 58%.

TFGBV has serious implications for the mental well-being of women and girls, including distress, anxiety, depression, and stigmatisation. TFGBV is a continuum of offline gender-based violence, rooted in negative stereotypes against women, gender inequality, and societal power asymmetry. The impacts of online gender-based violence go beyond the physical, psychological, and economic consequences that can affect women and girls. They can weaken democracy and women’s rights and cause self-censorship, social isolation, and withdrawal of women from the digital sphere.

Meta’s new content moderation policy raised legitimate concerns about the spread of harmful content against women and minorities - by loosening its enforcement, the platform risks enabling more TFGBV, which can fuel and exacerbate offline gender-based violence.

Looking ahead

We will continue monitoring the evolving online discourse targeting women and girls in the coming months. Our focus will be on identifying emerging patterns of abuse, assessing the impact of platform policy changes, and informing strategies to better protect vulnerable communities in digital spaces.